|

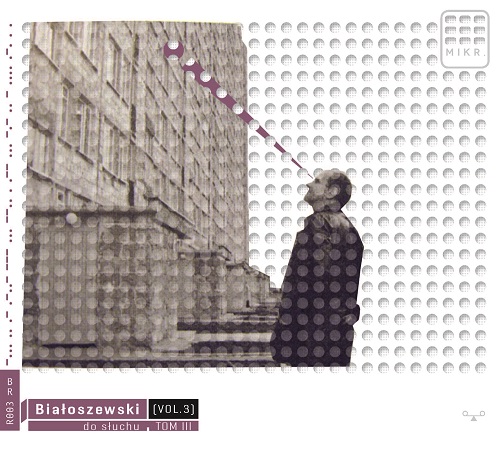

Białoszewski do słuchu, vol. 3 - Tower Block

|

Release Date: IV 2014; Współwydawca: Fundacja

Total Time: 68:11

1CD | 10 page folded insert | digipack

Miron Białoszewski – Blok: "Chamowo”, późne wiersze

1. 14 czerwca („Chamowo”)

2. Odczepić się

3. Moje nowe miejsce

4. Zbudowani, sklocowani

5. Przyszła Berbera na nowe mieszkanie

6. Szum

7. Czwarta z minutami („Chamowo”)

8. Wyrocznie, wieszczownie...

9. Jeszcze nie hiena

10. Na 9-tym piętrze siedzę...

11. Ile razy się mieszczę...

12. Siódma, ósma („Chamowo”)

13. Padało jak za Noego

14. Nowe cztery strony świata z Chamowa

15. Na pętli na Chamowie

16. Świtkiem 20 czerwca („Chamowo”)

17. Korytarz górny zapasowy...

18. Oprowadzanie

19. Stuki, warczenia, dokuczają

20. Późno... („Chamowo”)

21. Upał...

22. Na jedno tele

23. Stamtąd Siekierki

24. Portret na tle Siekierek

25. Sprawdzanie środka panoramy

26. Skąd tyle radości...

27. Wyszedłem na miasto... („Chamowo”)

28. Topola, świeci woda, kusi

29. Wróciłem i w okno...

30. Ciut później

31. Wtorek 15 lipca („Chamowo”)

32. Rusztowania zaskakują

33. W klatce, na klatce

34. – Ach, to rury dosłownie

35. Rano od początku lało... („Chamowo”)

36. Podniósłbym rękę...

37. Te niebiany

38. Boże, dokończ im tę szafę...

39. Uciekam zjeżdżam...

40. 16 listopada, niedziela („Chamowo”)

41. Zima z końca drugiego tysiąclecia

42. Po śniegu

43. (biały śnieg...)

44. (Jedni za drugimi – słychać...)

45. Na piszczałach grzejników...

46. Bili obok w ścianę... („Chamowo”)

47. Sufit biega na obcasach

48. Kawalerkę na Saskiej...

49. Przejechanie przez nowe

50. Oj ja wysoko

51. Ze ścianami na głowie

52. Z okienka

53. Puszczałem „Magnificat”... („Chamowo”)

54. Święte życie tu może być...

55. A jak cisza nie...

56. Wysiadam od Wisły...

57. Wchodzę w blok Eskich

58. Bez rusztowań...

59. Czwartek („Chamowo”)

60. Poryw

61. 3 kwietnia

62. (obeliskami bloków chodzi...)

63. Z wylęgu

64. Mamy mieszkać w domach

65. (na osiemnastym piętrze...)

66. 5 maja, środa („Chamowo”)

67. Wygląd w okno...

68. Rano sprawdzania i zapomnienia...

69. Nieproszoność minęła

70. Na gnieździe stoję...

71. 19 czerwca („Chamowo”)

72. Kwadratami ulic...

73. Niedziela rano

74. 27 czerwca („Chamowo”)

Text and voice: Miron Białoszewski

Recorded by Miron Białoszewski and Jadwiga Stańczakowa, Warszawa 1975-1982.

75. Marcin Staniszewski: "Chamowo”

Composed and performed by Marcin Staniszewski

Text and voice: Miron Białoszewski

The role of Miron Białoszewski was played by: Michał Mendyk, Robert Alabrudziński, Wojciech Bubak, Norbert Pęcherski, Andrzej Izdebski, Marcin Russek, Wojciech Boryczko, Roman Przylipiak, Piotr Świątkowski, Igor Pisarewicz

ZREALIZOWANO Z UDZIAŁEM ŚRODKÓW MINISTERSTWA KULTURY I DZIEDZICTWA NARODOWEGO

|

|

| I bought a tape recorder for four thousand. When you come to Warsaw in May or June, we could do some recording. It's a good activity. Interesting to everyone.

Miron Białoszewski, April 1965

|

In April 1965, Miron Białoszewski buys a tape recorder. He intends to record “A Memoir of the Warsaw Uprising” he is currently writing, and “test himself” by performing and registering his poems on tape. Since then, in the flat at Dąbrowskiego the reels often spin, while Białoszewski reads, dictates, recites and sings to the microphone. Apart from “A Memoir...” which is entirely dictated into the tape recorder and then typed down “by ear”, in the next 2 years, he registers works of Mickiewicz, Słowacki and Norwid, fragments of the Gospel of Matthew, “Stabat Mater” and “Dies irae” hymns in his own translation, poems from the collections “The Revolution of Things” and “Było i było”, vespers sang together with Leszek Soliński and private conversations with friends.

Białoszewski treats the tape recorder as both a work tool and a toy, a gadget used for entertainment, whereas recording itself becomes a substitute for ever regretted performances of the home theatre he's been planning to revive since the closure of Teatr Osobny in 1963. In the course of time these plans appear decreasingly feasible, his works on “A Memoir...” are almost finished and Białoszewski ceases writing poems in favour of his dedication to prose. His enthusiasm about tape recording diminishes and finally, he quits the activity for quite a few years.

In the mid 1970s, his interest in it is aroused again due to the poet's acquaintance with Jadwiga Stańczakowa. In order to secure his blind friend free access to his works, Białoszewski decides to record them on tapes on a regular basis. This time recording sessions take place in Jadwiga's flat by her portable tape recorder Grundig MK 232. For the next few years, right after writing a new poem or a fragment of prose, Białoszewski – sometimes in the middle of the night – arrives at Hoża and, as Stańczakowa recalls, “in rupture and exhilaration – he records it all”. This is how this intriguing practice is established: the author's first reading of the text aloud and its recording on tape complete and finalize the process of writing. By 1982, the majority of the poet's late output is registered on tapes: hundreds of short poems, “Chamowo”, “Zawał”, fragments of “Rozkurz” and “Tajny dziennik” as well as “A Memoir of the Warsaw Uprising” and “Szumy, zlepy, ciągi”. Many of his works are recorded by Białoszewski in the professional studio of the Polish Radio which, at Stańczakowa's instigation, he often visits from the mid 1970s.

This way, during the 17 years an unusual sound archive is created – an archive which constitutes a remarkable phenomenon in the Polish culture, both due to its volume (12 preserved tapes from the 1960s and several dozen tapes recorded in Jadwiga Stańczakowa's home altogether add to over 80 hours of materials, without even counting those maintained in the radio archives) and with regards to the nature of those recordings and their place among other Białoszewski's accomplishments. They are closely related with his characteristic vision of literature.

“I strive for the written to register the spoken. And I wish writing wouldn't eat speaking. What is found valuable in the spoken language, gets written down. What is valuable in the written language, is then spoken out loud”, he wrote in “Mówienie o pisaniu”. He called the invention of quiet reading a misunderstanding. He also declared, “I always considered poetry as something to be read aloud […] Poetry reaches its full being when it is spoken out loud.”

If, according to Białoszewski, a poem only starts to fully exist in being performed aloud, it is the recordings that give us the fullest insight into the matter of his creative output and let us truly see how these texts were intended by their author. Graphic notation is merely a score requiring a complementary voice, while proper pieces should be “fully heard”. This is confirmed by Białoszewski's own performances recorded on tapes. The author uses tempo, rhythm, the voice volume and melody with intensity to be rarely encountered in the Polish tradition of poetic readings, and thus he makes the sound one of the basic dimensions of his texts.

Despite the above, in reception of Białoszewski's output, the recordings have not occupied a position they deserve. Kept as a part of the collection of the Museum of Literature in Warsaw, they are only known to the small circle of experts and the poet's close friends. The series “Białoszewski by Ear” is the first to bring them to light and make them available to the wider audience.

***

I fall asleep in the morning with difficulty. I can't get used to the acoustics of the new home. These walls, ceilings emit additional ringing echoes. Yesterday, I unexpectedly heard my own record in the room – unpleasantly, with the after-echo as if made by a melodic hammer.

Miron Białoszewski, “Chamowo”

On June 14, 1975, after 17 years of living on the Dąbrowski Square, Białoszewski moves to Praga – to the periphery of Saska Kępa called Chamowo. A cosy old building in the city centre gets replaced by an enormous, newly built 11-floor block of flats that stretches for 250 metres along Trasa Łazienkowska. For the 53-year-old poet, this forced move is an unwanted life revolution which he receives with reluctance and fear, even though for the first time in his life, he earns a flat just for himself.

The change of environment and related experiences stimulate Białoszewski as a writer. In the following year, he writes Chamowo: a novel-like journal where he describes the process of getting accustomed with his new place. He also goes back – after a few-year break – to writing poems. During the year, his prose and poetry constitute a unified stream whose main theme turns out to be the experience of living in a block of flats. The same events, observations and motives become the origin of concurrently written fragments of the journal and poems which happen to double but also complement each other.

In these texts, Białoszewski receives the world that surrounds him with great intensity. He can look at it as if he saw it for the first time – in a fresh, unprejudiced manner turning even the most ordinary element of the everyday life into a fascinating discovery. The simple act of looking out of the window from his flat on the ninth floor acquires a quality of an aesthetic adventure, while a long emergency corridor linking staircases turns into a mysterious cinematographic space where anything can happen. However, the outstanding sensitivity to stimuli is interconnected with exceptional sensual vulnerability. In his new flat, Białoszewski is attacked by unpleasant smells leaking in through the door and windows and most of all, by sounds persistently heard through the walls and the ceiling. Unidentified clutter and rumble, party singing, sounds of conversations and the radio, droning of airplanes flying by and vacuum cleaners used upstairs, ringing of the bells from the school nearby, sounds of workmen on the scaffold – these are only some of them. The acoustics of the block becomes one of the principal subjects of “Chamowo” and the poems written in this period. They contain recurring images of Białoszewski who runs around the staircases in search of the source of an annoying sound or escapes from his flat to avoid importunate noise. The sense of hearing begins to play a much more important role in his writing than ever before which is reflected also in the sound level of his texts: since Białoszewski moves to Chamowo, many more purely sonic elements like exclamations, onomatopeias or emphasized single sounds appear in his poetry. Some of these poems are virtually sound mini-etudes.

The recordings of these works performed by their author survived on tapes because, shortly before moving, Białoszewski started to register his texts for Jadwiga Stańczakowa. Thus prose and poetry pieces written in Chamowo were regularly recorded, soon after being created. Readings registered on tapes are their premiere performances in front of the one-person audience. In order to present them to Jadwiga and to the microphone, Białoszewski took trips to the other side of the river, to Hoża Street. In a certain way, in his blind friend he found an ideal addressee for whom the basic medium of contact with literature was the voice.

The entire text of “Chamowo”, read fragment by fragment, was recorded on 20 tapes. Years later, they helped establish the final shape of the text before its publication.

The recordings presented in the album “Białoszewski by Ear – Volume III” come from 20 different tapes from Jadwiga Stańczakowa's collection. Most of them were recorded in the years 1975-76 but there are also some posterior materials among them. Other poems distinguished by their sound quality which focus on the experience of living in a block of flats were included in the album “Białoszewski by Ear – Volume IV”.

Maciej Byliniak

***

The aim of the composition "Chamowo" was to present the world of a man beset with the sound magma typical of everyday life in a block of flats. Białoszewski was extremely sensitive to light and sounds. At the same time, he was fascinated with rustle, eletric hum, echo and buzz which he expressed in numerous onomatopoeias. Therefore, I assumed a role of a ”human antenna” receiving the tiniest rustle and amplifying it to the unnaturally high sound volume. In the recordings, I used a whole range of tools – beginning with a modular synthesizer controlled by Białoszewski’s voice, through granular synthesis and field recordings, to algorhytms which enable the utmost extention of a given sound. Like in the case of the word ”time” which – extended over one thousand times – constitutes the background of the entire piece as it imitates the sound of humming radiators encountered in old housing estates. The whole composition carries traces of the past – owing to the impulse response technology, it was possible to transpose the acoustic texture of Białoszewski’s original recordings to modern sounds.

Marcin Staniszewski |

|